This, I think, contributes to the pendular nature of campaign reporting, where you will get a week or two of coverage that seems to favor one candidate, followed by a subtle shift in positive coverage to the other candidate for a time. At work is a positive feedback loop, similar to the one that drives the booms and busts of a speculative market: positive motion gets reported as positive news, and positive news in turn drives positive motion, and so on, creating a sort of media bubble. But the higher that bubble wafts, the more routine and expected--and not-newsworthy--it becomes that the candidate will do well, thus causing the engine that drives the bubble upward to run out of steam. In the meantime--and because of the zero-sum nature of campaign coverage in a two-party system--expectations for the other candidate will be so low that any modest improvement results in a large vector of movement, which will result in significant positive news, in turn causing more positive motion, etc., until this other candidate becomes the one propelled by a bubble effect.

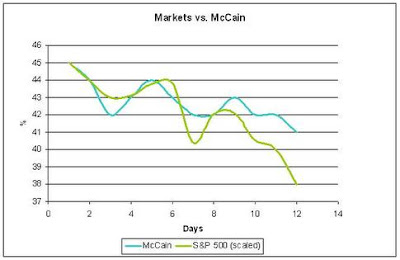

This process, though, only seems to occur in the absence of hard information that would otherwise be driving each candidate's fortunes. As bloggers like Ezra Klein and Matt Yglesias often observe, what decides elections is not this or that gaffe or campaign ad, but rather external events, like financial collapses or terrorist attacks. But this, again, is similar to what we see in markets: a speculative market occurs when there is uncertainty: people start using the behavior of others as a proxy for real information, piggy-backing on their presumably sound analysis, and the result is a herding effect. But when some real information emerges, the market reacts to it and prices quickly snap to reality. In this campaign, there has been an abundance of "real information" generated by the unfolding economic crisis, and so voters are responding to this rather than piggy-backing on the analysis of campaign reporting. As a result, the fortunes of the candidates has been marked not by the boom-and-bust cadences of campaign reportage, but by the performance of the stock market (which for many is the de facto barometer of economic health), which this chart from Ezra Klein strikingly illustrates:

It is worth mentioning as an aside that all of this explains why the McCain campaign is desperately--and futilely--trying to change the subject away from the failing financial system. So long as the election is determined by outside events, the McCain campaign is powerless to help its candidate win.

No comments:

Post a Comment