I got momentarily excited by Conor Friedersdorf's insistence that I read one Jim Manzi's "manifesto of sorts" that lays out a "framework for understanding the challenges that America faces". I was promised that his would be a "serious voice" that moves us beyond "bromides about liberty and tyranny" that you typically hear from the right these days.

I got momentarily excited by Conor Friedersdorf's insistence that I read one Jim Manzi's "manifesto of sorts" that lays out a "framework for understanding the challenges that America faces". I was promised that his would be a "serious voice" that moves us beyond "bromides about liberty and tyranny" that you typically hear from the right these days.Anyway, I read the thing, and was unimpressed. Far too high-level and vague to be of any use to anyone, it strikes me more as a formulation of right-wing conventional wisdom and political narrative than any real attempt to deal with substantive issues or engage the opposition in an intellectually honest way. He passes comment on things like the bailout of Wall Street and the nationalization of GM without any sort of discussion of what the consequences would have been if those actions had not been taken; he pooh-poohs cap-and-trade as "economically extravagant" (which is something of a non sequitor, I might add) without addressing the costs of not regulating carbon output; he utterly fails to address military spending as a component of the government's precarious long-term financial position; he urges the repeal of fiscal stimulus without offering an alternative approach to alleviating America's 10% unemployment rate; he offers no way forward on health care reform.

If his goal with this essay was to engage in a productive way on any of these fronts, I'd say he failed. If you're going to dismiss cap-and-trade, for example, you have to at least address why you think it's a bad policy--whether that means a critique of the way the policy will be implemented, or empirical skepticism about the dangers of global warming, or whatever. But Manzi offers no such arguments; just blank, high-level assertions that seemed to be backed by nothing other than implicit conservative conventional wisdom.

In any case, here are a few specific things that I think Manzi either mischaracterizes or doesn't address:

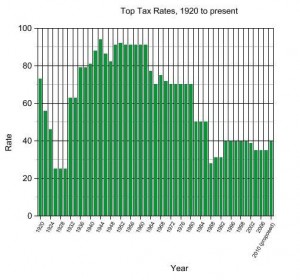

- He mainly frames America's politics as a tension between Great Society liberal welfare statism and Reagan-era economic deregulation, but I think this picture is no longer accurate today. In the first place, it's not the case that today's liberals are fighting to undo the Reagan revolution: Reagan won that war, and liberals conceded long ago. To see this, just check out what marginal tax rates were like before and after Reagan took office:

During the Great Society era top marginal rates were up around 80%; by the time Reagan took office they had already been coming down quite a bit, but part of Reagan's legacy is that that level of taxation is permanently off the table. Of course, taxation is more than just the top marginal income tax bracket--but I find this to be a useful barometer for the overall level of taxation a population is willing to bear. Keep in mind that accompanying this were decreases in the capital gains tax and, at the state levels, significant rolling back of property taxes, following the Prop. 13 "tax revolt" in California. No serious liberals today propose we fully reverse these cuts and return to Great Society levels of taxation, and even the mainstream Democratic establishment favors pro-market policies such as free trade and economic incentives such as cap-and-trade rather than direct government regulation and intervention. We live in a supply-side America.

Secondly, not only is the conflict that Manzi sets up already resolved, but he misses the crucial point that the fiscal sins that have occurred since Reagan have been largely perpetrated by the Republican party and (too many) centrist Democrats. I don't want to make this too partisan a point, so maybe I'll just say this: since Clinton took office, we've seen the California-fication of the federal government, where de facto supermajority requirements in Congress--the Senate specifically--make it impossible to implement tough decisions (like increasing taxes or cutting entitlements), and yet still allow politically popular spending initiatives to go through (like Medicare Part D and the Bush tax cut). By the time the financial crisis hit, and Bush was forced to pass a stimulus bill and a Wall Steet bailout (yes, Bush did both those things; Obama then passed a second, far larger stimulus bill), the US found itself badly overextended, and with mounting health care costs to boot.

So the narrative is not Great Society social cohesian vs. Reagan supply side economics forever dueling for our national soul; it's more like, Reagan wins, then the Republicans totally lose their bearings and abandon conservative fiscal principles while in power, and then meanwhile leverage an increasingly disfunctional Senate to obstruct any Democratic reforms from coming through. - Manzi shows here he doesn't understand the rationale for stimulus spending:

Only about 5% of the money appropriated is intended to fund things like roads and bridges. The legislation is instead dominated by outright social spending: increases in food-stamp benefits and unemployment benefits; various direct and special-purpose spending relabeled as tax credits for renewable-energy programs; increased funding for the Department of Health and Human Services; and increased school-based financial assistance, housing assistance, and other direct benefits.

The point of stimulus spending is to increase overall demand in the economy. You can do this by building roads and bridges, yes, but you can do it just as well by, say, lining the pockets of a poor person with some cash that he will be certain to spend in the near future (like, say, on food). What matters is the stimulative effect of the spending, not on whether the spending happens to be on infrastructure or more welfarish services. - More:

All told, finance, insurance, real estate, automobiles, energy, and health care account for about one-third of the U.S. economy. Reconfiguring these industries to conform to political calculations, and not market-driven decisions, is likely to transform American economic life. And the fiscal consequences of the spending involved will be enormous. The federal budget deficit for 2009 was about 11% of gross domestic product, which is far higher than any the United States has experienced since World War II. This deficit spending is the real stimulus. Something like 10% of all the economic demand in the United States is supported by government borrowing from the future, which is essential to propping up the current "recovery."

Gah. Where to begin. First: "This deficit spending is the real stimulus." That. Is. The. Point. The whole point of fiscal stimulus during a liquidity trap (i.e., when the Fed's interest rate is at 0% and cannot be lowered any further) is that the government's deficit spending props up demand until the economy gets going again. It's no big secret that stimulus spending is deficit spending. Second: nobody is reconfiguring the real-estate industry. Nobody--and it's a shame, really--is reconfiguring the finance industry. As for energy, cap-and-trade is a market solution--no different in principle than a carbon tax. Health care you can make more of a case for, obviously, but it's also true that a) the government already accounts for a high percentage of medical spending in the US, since we have, you know, socialized medicine for everyone over the age of 65, and b) the whole aim of the current health care reforms is that they will reduce the deficit over the course of a ten year time frame. Third: in economic terms, there's no difference between a recovery and a recovery with scare quotes around it--a recovery is a recovery, a job is a job. Conservatives seem to have this thing where a recovery fueled by government spending is somehow "artificial", or that jobs created by the government aren't real "jobs" (make-work, I think the term is they use). But this isn't a meaningful distinction at all (that said, I think you really can call the current recovery a "recovery", not because it is propped up by government deficit spending, but because it's a jobless recovery--asset prices are coming back up--yay Adobe stock--but unemployment remains sky-high at 10%--boo human misery). - Here Manzi makes some proposals without giving an ounce of thought as to their consequences:

we must unwind some recent errors that fail to take account of these circumstances. Most obviously, government ownership of industrial assets is almost a guarantee that the painful decisions required for international competitiveness will not be made. When it comes to the auto industry, for instance, we need to take the loss and move on. As soon as possible, the government should announce a structured program to sell off the equity it holds in GM. Similarly, the federal government should relinquish direct control of banks and insurance companies. Moreover, one virtue of the slow rollout of spending under the stimulus bill is that most of it can be stopped — and should be.

Look. If these were normal times, and GM was going under, you know what? I'd be as solemn as the next guy in saying that it should die a natural death. But these aren't normal times; these are perverse times. Here is what I think happens with folks like Manzi: in normal times, we get accustomed to the idea that markets, among other things, give you information: if the price of apples goes up, that tells you something about the supply and/or demand for apples. If a business goes under, that tells you something about the quality of its products and/or the efficiency of its processes. If an individual or company goes into debt, that tells you something about the financial decisions about that individual or company. In other words, though the market may cause pain--for example, the slow death of the American auto industry--the pain is justifiable, and in the long run it's better for everyone to suffer the pain now and move on so that the overall economy can continue to perform at a high level. And I'm more or less fine with all that. But the thing is, all that's only true in normal times, when markets are functioning. But when the financial crisis and recession hit, markets stopped functioning properly. Prices no longer reflected value; they reflected the fact that everyone was selling in a panic at the same time. Companies started failing, not because their products were of low quality or inefficiently made, but because they could not get the credit they needed to keep their business running. Saving, in normal times a virtue, suddenly became a collective vice, as the force of everyone pulling back spending caused demand to drop and the recession--and unemployment--and the condition of everyone's pocketbooks--to worsen. As Paul Krugman likes to say, we're through the looking glass--markets are no longer giving us good information about the real world.

And so you can't just cut GM off. Because, even if GM deserves to die, surely other car manufacturers with factories in the US like Toyota and Honda don't deserve to die, too. And yet that's exactly what could have happened if GM went under, because of a "supply shock"--the companies that sell parts to GM would have gone under, and the assembly lines of the other companies they sell to would have ground to a halt--which, in the midst of the worse recession since 1928, could have led to scary results indeed. And you can't just unilaterally sever the government's stake in the big financial entities like AIG--because this could trigger a panic and another financial meltdown.

Finally, you can't just revoke the stimulus. Or, if you do, you better tell a damn good story as to where the demand is going to come from that's going to lift this economy back up and bring unemployment back down. Everyone agrees that normally, with a non-zero interest rate, you would lower that rate and induce spending and investment that way. But we're at 0%, and can't cut the interest rate. So rather than inducing demand, we're straightforwardly creating it via federal deficit spending. The spending will roll out over the next couple of years, but, that's okay, because unemployment will remain high for at least that long. So you think this is a bad idea? You think the underlying economic principles are unsound? You think perhaps that stimulus won't have a significant impact, or maybe, alternatively, that the costs of a higher deficit outweight the benefits of stimulus? Fine. But tell us what your argument is. - ...

Well, this post is getting out of hand--I think you all get the picture. But let me be quick to reiterate: I don't think Manzi's essay is lacking because I disagree with its conclusions. I think it's lacking because it doesn't offer any arguments against opposing views or explain in any discernible way the rationale for its own views. Hopefully, either Manzi or someone of his ilk will get around to making a case that we can all sink our teeth into.

No comments:

Post a Comment