Although I disagree with some of the phrasing that he uses--clearly, even those who favor bombing Iran do not do so because they "want to slaughter" innocents, as he seems to imply at one point--I think Glenn Greenwald makes a very, very good observation:

Hopefully, one of the principal benefits of the turmoil in Iran is that it humanizes whoever the latest Enemy is. Advocating a so-called "attack on Iran" or "bombing Iran" in fact means slaughtering huge numbers of the very same people who are on the streets of Tehran inspiring so many -- obliterating their homes and workplaces, destroying their communities, shattering the infrastructure of their society and their lives. The same is true every time we start mulling the prospect of attacking and bombing another country as though it's some abstract decision in a video game.

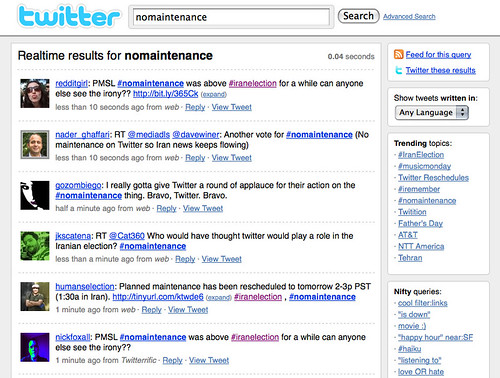

Humanizing is right. Although it's a bit of a cliche at this point to refer people to the #iranelection tag on Twitter, I think it actually shows pretty well how these social networking sites enable Americans to become exposed to--and emotionally invested in--whole groups of people who would otherwise remain foreign and abstract.

It makes me wonder, a bit, how things would have been different if Iraqis had been able to communicate this effectively in the run-up to the war in 2003. Suppose that when their homes and neighborhoods were bombed, they emitted a steady stream of horrifying pictures and videos? Suppose that they directly entreated us to stop raining death down upon them from above with Facebook groups and hashtags? Even as I write that it seems kind of dumb, but, still: isn't there something very powerful about one person saying to another, in whatever medium: please don't kill me and my family?

The post title is a paraphrase of a great Jack Handy line, that questions whether we would be so quick to cut down trees, if they could scream. Unfortuneately, I have a feeling that the same principle applies to people. Before the internets, it would have been nearly impossible to have any kind of meaningful, personal, and affecting interaction with someone on the other side of the world--and, as a consequence, the snuffing out of tens, even hundreds of thousands of lives would enter into our brains as bare factual information. Psychologically, we wouldn't "hear the screams".

So maybe this is the "Kantian turn" in the ongoing discussion about what, if anything, the role of sites like Twitter are playing in the Iranian civil unrest. The change isn't taking place within Iran; it's taking place within our brains.

(Photo by natachaqs)

No comments:

Post a Comment